Price hikes on content — and then what?

Posted by Steve Gray

As more and more newspaper companies charge more and more for their content, it’s important to ask — how are they using the money?

Charging more for content seems to be a strategy whose time has come. As of the last counts I could find — dating back to early last year — Pew was reporting more than 150 U.S. newspapers had adopted digital paywalls or meters, while the Associated Press was reporting more than 300. And that’s old data. Since then, reports of new paywalls and meters in the U.S. and around the world have continued at a steady clip.

The reason is obvious. Advertising revenues on the print side continue to fall, and ad revenues on the digital side aren’t making up the declines. Rather than continuing to cut costs dollar for dollar, media companies are turning to the consumer — starting to charge for digital content and ratcheting up prices on the printed product.

There’s a growing realization that consumers who really want the content will pay more than our industry — particularly in the U.S. — has had the audacity to charge. So, at Morris and elsewhere, digital meters and paywalls are just one leg of a plan that centers on charging everyone more for our content than they’ve paid in past.

At Morris, we called it “All Access.” In the last year, across our newspapers, we’ve been raising print subscription rates an average of nearly 20%. With the price hikes, we have announced that each subscription would now include full access to all our content across all channels, both print and digital. That required us to start metering our web and mobile news channels.

At the same time, we announced improvements in coverage and content and a new subscriber rewards program. And, to make sure we continued to reach those who dropped out, we beefed up our free alternate delivery products in desirable distribution areas. In most of our markets, this includes opt-in delivery of inserts on weekends — the “Sunday Select” model. And we implemented digital-only subscriptions priced at a substantial share of the print subscription rates.

In all of this, we drew heavily on the example of the Dallas Morning News, which had been on a similar path through several rate increases and had proven it would work. By the end of 2011, they had arrived at seven-day subscription rates of almost $40 a month — more than twice our average rate at the time.

They had proven what we had barely dared to hope — that the ridiculously low consumer prices charged by American newspapers were not the limit.

For us, the result of the program so far has been millions in additional revenue across our 12 daily papers, and — not surprisingly — a further erosion in print circulation. The tradeoff has been acceptable so far, and the new revenue has been extremely helpful.

Why it works

The program doesn’t work because lots of people are willing to pay for digital content. The number of digital-only subscribers, while growing, is still relatively small.

The program works because so many print subscribers still want the printed product and will pay more for it. Some of these folks use our digital products, but a great many don’t. They just want a good, solid printed product. And Dallas has shown that the price ceiling is still somewhere above our current rates.

Figuratively, it’s as if we and others in our industry had discovered a hidden annuity containing millions of dollars in untapped consumer revenue. And now we’re making withdrawals.

But there’s a limit to it. Each price increase will shake off more consumers, reducing our advertising distribution footprint. For now, free-distribution channels like Sunday Select can be used as a surrogate for paid circulation to keep preprint revenue up. But the penetration of ROP advertising keeps going down as paid circulation declines.

And how many more times can we raise prices before exhaust the consumer’s willingness to pay?

Reaching the ceiling

At some point — maybe two or three increases from now — the returns from new rate hikes will only equal the lost revenue from those who drop their subscriptions. At that point, the increases will need to stop. The annuity will be maxed out.

Why? Because 1) the people who will pay a lot for print are getting steadily older and fewer, and 2) the willingness to substitute free Internet content for paid content grows as our prices go up.

Meanwhile — except for special cases like the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the New York Times — few papers are seeing any huge numbers of people willing to pay for digital content.

Looking ahead

In the next few years, each further price increase will seem like a sound business decision that’s needed to keep meeting payroll and providing income to shareholders.

But if that’s all we do with the money, we’re backing ourselves into a death trap.

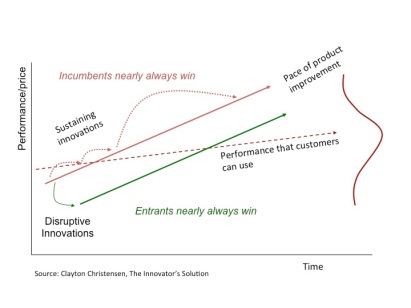

We’ll be exhibiting the classic behavior of all disrupted industries. As the competition gets tougher, the disrupted business retreats up-market by focusing on its best customers — the ones who will pay the most.

Meanwhile, the non-customers at lower end of the market get priced out of the product and find ways to satisfy their needs with less expensive solutions.

Meanwhile, the non-customers at lower end of the market get priced out of the product and find ways to satisfy their needs with less expensive solutions.

This pattern was discovered and documented by Clayton Christensen in his book, The Innovator’s Dilemma. It was a foundation stone of the Newspaper Next project I led back in 2005-2006.

In every disrupted industry, the business gets tougher and tougher as low-end competition increases. Revenues decline, boosting the pressure to raise prices and improve quality just to stay profitable at expected levels.

The paradox

It’s not necessarily wrong to raise prices, if your customers will pay them. But in a disrupted industry, if the revenues are used just to stay alive another year, it’s a dead-end street. There comes a point where the next increase is impossible. Then the only choice is cost-cutting — painful shrinkage — that may lead on toward oblivion.

For our industry, in consumer pricing, I believe that point lies only two or three years ahead.

What we need right now, while there’s still time, is a disciplined dual strategy: 1) Use part of the revenues to sustain the business, and 2) Use the rest of the revenues to develop the next-generation business models that will be needed to replace the declining revenues from the core business.

A number of newspaper companies are doing this. One of the most common points of investment is in new digital sales and marketing strategies and structures. Some, like Belo, Morris, Gatehouse and others, are investing part of their current cash flows to create or acquire substantial new digital-only sales businesses focused on SMBs who don’t advertise in newspapers. Some are investing in new audience strategies, too, or buying digital ad agencies and other ancillary businesses that have opportunities for growth.

If your company isn’t making new investments right now to tap parts of the business and consumer markets you haven’t been reaching, it’s time to rethink your strategy. Your annuity is running out.

Posted on August 20, 2013, in Audience, circulation, Consumer revenue, Disruption, innovation, investment, Media business model, Paid content, Revenue and tagged audience, business model, circulation, Clayton Christensen, consumer revenue, content, content meter, disruption, innovation investment, media business models, media disruption, newspaper, Paid content, paywall, pricing, revenue. Bookmark the permalink. 2 Comments.

Daily newspapers should be no more than 25 cents and Sunday papers with coupons should be no more than a dollar. Retail outlets need at least 15 cents and 25 cents respectively. Advertizing should pay for the cost of print, distribution and salaries.

LikeLike

Years ago I worked for the Albany Herald. The owners wanted to raise the price. We were currently charging just under $10 per month and our circulation was at 33,000. We were able to hold off the increase for about a year and then we were force to raise the price. Several of us left at that point and two years later circulation had fallen to less than 30,000 and the projected profit increase had disappeared.

LikeLike